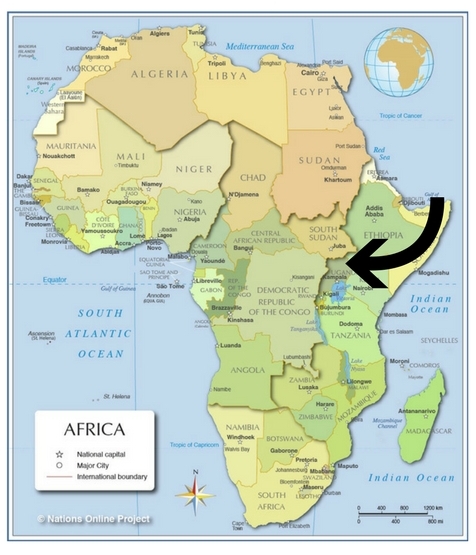

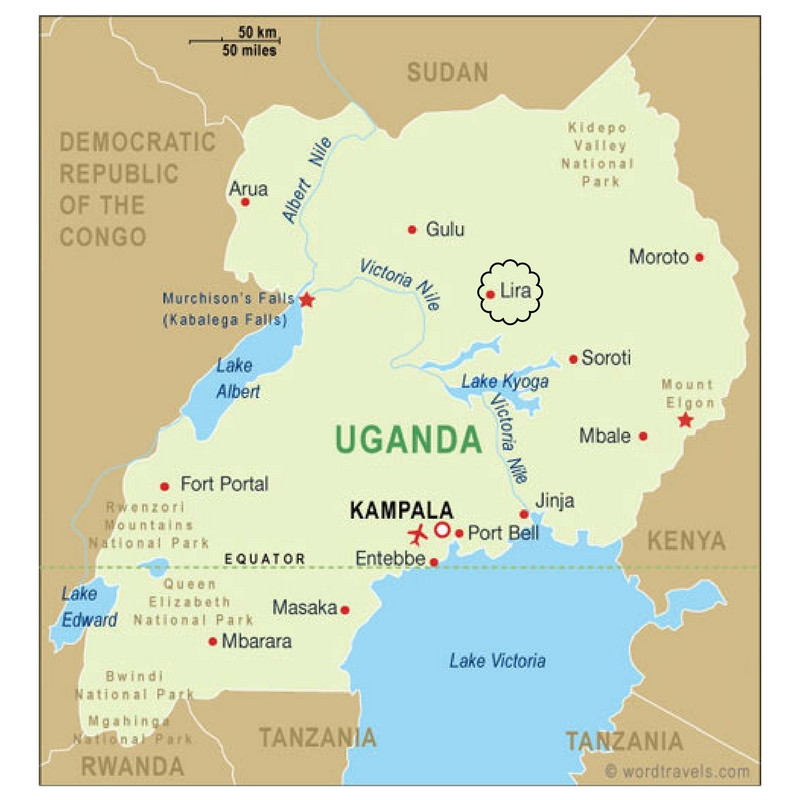

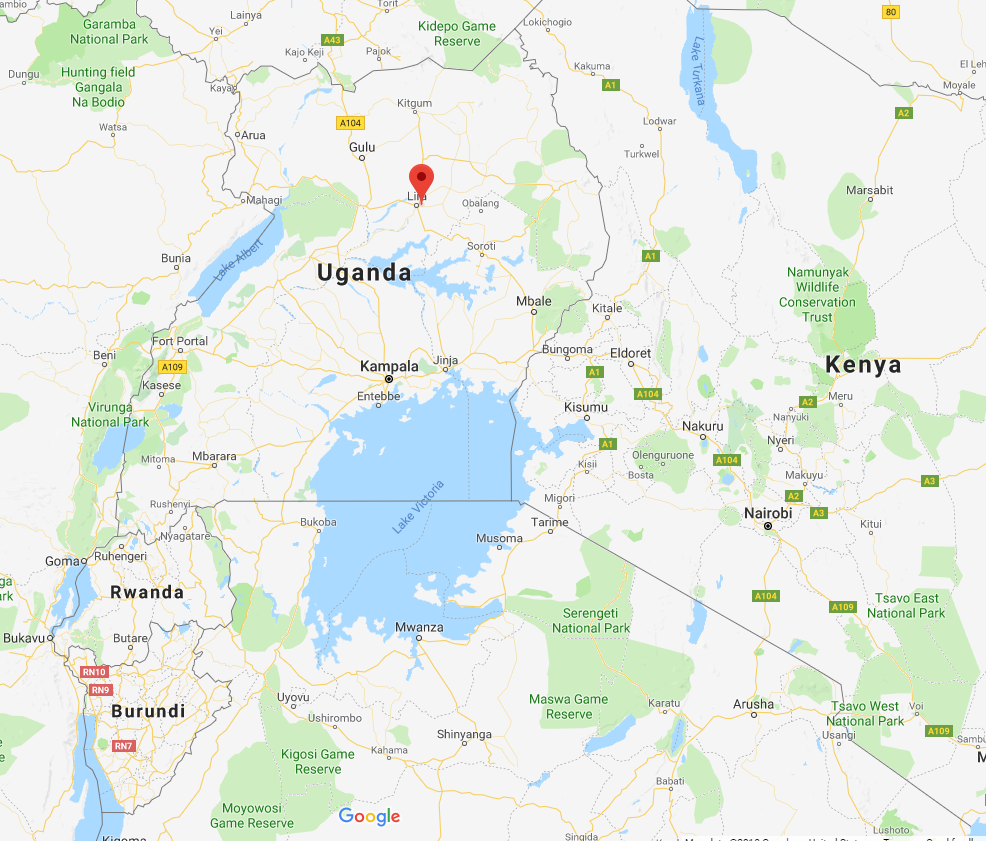

For some context, this blog reviews where African Girls Can operates – from the bird’s eye view of Uganda to a closer look at the rural northern part of the country where our students come from and attend school. Together, let’s learn something about this region, its people and its culture. For those who have not been there, we are going to try to paint a picture for you.

Uganda

Uganda is a country in East Africa that is the size of the state of Oregon. However, unlike Oregon, which has just over 4 million residents, Uganda currently has an estimated population of 45.7 million. There are 56 tribes and 42 indigenous languages. (Again, all in the space of Oregon!) English was inherited during the colonial period and the school system is also a remnant of British rule (which ended in 1962). Source

There are 1.4 million refugees in Uganda, mostly from the neighboring countries of Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan. 1 million people flowed into the country just during the time period from mid-2015 through 2016. Source

This population explosion also means that there are lots of children and young adults. 78% of Uganda’s population is under the age of 30. Nearly half is under the age of 15. This age disproportion clearly impacts a country’s ability to educate its youth to become productive, fulfilled citizens who can contribute to society. Source

A Terrible War

There was a civil war with the Lord’s Resistance Army from 1987-2007 in northern Uganda. As a result of this conflict, 100,000 people died and nearly 2 million were displaced. Child soldiers and other abductions (including 139 school girls from St. Mary’s School in Aboke in 1996) characterized this heinous war, with upward of 75,000 children kidnapped.

While the war ended 12 years ago, the entire region is still in a phase of recovery. Attempts to recover property have been very difficult. People suffer from PTSD and the rate of HIV infection is high (estimated 10% of women aged 15-49 are HIV+, p 129). Our girls may not remember the horrors of this time, but their parents certainly do. Everyone knows someone who died.

“One of the biggest challenges during and post-war was accepting the children fathered by rebels when they returned from the bush… Peers who escaped abduction shamed returned girls even though the atrocities they suffered were through no fault of their own.” (p 29-30)

“Post-war poverty has caused parents to return to their original belief of supporting only boys at school and forcing girls into early marriage. When parents can marry off girls at early ages, they no longer need to provide for their education or welfare.” (p 32)

Before the war, “family life was valued, and evening story-telling around fire pits was a cherished tradition for bringing extended families together and for teaching children cultural values and beliefs.” (p 27)

Lira and Otuke Districts

Lira, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary as a trading center in 2019, is the location of St. Katherine Secondary School, the boarding school the students attend. Their homes and families are in the neighboring district of Otuke. Each district has numerous sub-counties and literally thousands of small villages scattered in the countryside.

The people from this area are Langi, which is the 6th largest nationality in Uganda, and their native language is Leblango.

Langi values include “respect and dignity, hard work, independence, honesty, equality and equity.” (p 126)

The fertility rate is 6.3 children. (p 129)

“Most people from these districts were, and still are farmers, although most cultivate cops on a small scale, mainly for home consumption.” (p 28) Every one of our school girls talks about “digging in the garden.” (90% of rural Ugandan women work in agriculture, yet in 2013 they received less than 10% of extension services and credit, and they owned only about 7% of the land. p 69-70).

The quality of life in this area before and after the civil war is striking. Before the war, the people of Lira kept cattle as a major source of wealth. Income came from the cows’ milk and skins and the animals could be sold for school fees or given as part of a bride price. “Most families lived above the poverty level. They could afford two meals a day and have their children in school. Because farming was carried out on a larger scale before the war, and the majority of families owned cattle.” (p 63)

“Poverty, high level of illiteracy, cruel treatment by their spouses, and denial of the right to property now characterize rural women’s lives.” (p 47)

More people have cell phones than flush toilets. (p 23)

Because literacy is low, community radio is the best form of up-to-date reports and information. It also is a means for reducing the culture of violence that began during the war. For instance, Okite Emma has a “Gender Program” on Radio Rhino, where she encourages better communication between men and women and teaches people better ways to manage the stress in their lives.” (p 121)

“Major international aid organizations and NGOs have departed from northern Uganda to pursue more recent world crises.” (p 72) This leaves a void that community organizations must fill. And, to do that, educated people, especially women, are needed.

Schooling

Approximately 50% of the children in this region are not in school, despite Uganda’s adoption of Universal Primary and Secondary Education. (p 80))

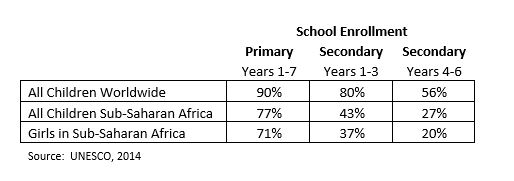

As children advance from primary to lower secondary and finally to upper secondary, the numbers dwindle (picture a funnel). While tremendous progress has been made in reducing the disparity between girls and boys in education at the primary level, girls still lag behind boys in secondary school enrollment and completion. It is our sincere hope that these numbers have improved in recent years, particularly for girls, but this is the latest data that is available.

In 2017, 33.5% of girls throughout all of Uganda completed their fourth year of secondary school, but only 21% advanced to S5/A-Level. (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2018)

Girls in towns and cities are more likely to continue past primary school than girls in rural areas like Otuke who have very little opportunity. For every 10 boys enrolled in secondary school, there are only 5 girls. Most of those girls do not stay in school for a variety of reasons. Fewer than 11% of girls there complete this level of education. (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2012) Enrollment at St. Katherine, which has over 1,000 girls, mirrors this. A-Level students (last two years), comprise less than 15% of the student body.

2018 Global Education Monitoring Report – Gender Review

Some additional, eye-opening statistics relating to girls in northern Uganda:

- 21% of girls attend secondary school.

- 20% are married before their 20th birthday.

- 35% are mothers before their 18th birthday. (p 129)

“Girls are viewed as a source of labor and income for the family. They are expected to help their mothers with domestic work such as washing, cooking, fetching water, weeding, and taking are of the younger children at home while their mothers are away. Therefore, even with Universal Primary Education, their attendance in schools is sporadic, resulting in poor performance.” (p 49)

These are deep seeded cultural beliefs that require engaging parents, especially fathers, to change views. “There is a need to convince fathers so that they can come to understand the value of educating girls.” (p 50) “A bride price is fleeting, while an educated daughter can bring about a lifetime of additional income.” (p 55)

It is hard to attract educated people to the field of teaching as being a teacher at a government school in rural Uganda is so difficult. It is crowded and chaotic, with kids that come and go. In 2017 there was an average of 75 students per classroom in Otuke, and 35 in the capitol city of Kampala (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2018).

The majority of teachers are male (few female role models for students). They often go unpaid, or they may wait for several months to receive a small wage. The average teacher salary in Northern Uganda is less than 300,000 Ugandan shillings/month ($82). There is inadequate housing for teachers near rural schools and some walk several miles each way. (p 56) The private sector has invested in education as a business and the best teachers have moved to private schools with better incentives.

Lack of private toilets, clean water and sanitary supplies are additional obstacles to continuing school for girls, once they reach puberty.

St. Katherine is a government-funded boarding school founded in 1958 with just 45 students. It became girls only in 1975 and now has a student body of over 1,000 students. The largest percent are Ordinary Level (S1-4) and a small minority are Advanced Level (S5-6). The girls are not allowed to speak their native language, but must speak in English or Leblango, which is a big adjustment.

A Hopeful Future

The people of this region are extremely resilient. “It would be easy to sink into despair after losing family, land and the few possessions they owned prior to the war in this already high poverty region, and many have. However… many have risen above despair to act for a better future for northern Uganda.” (p 3) People do “not allow the death and destruction of the past to hinder their hope for the future.” (p 8)

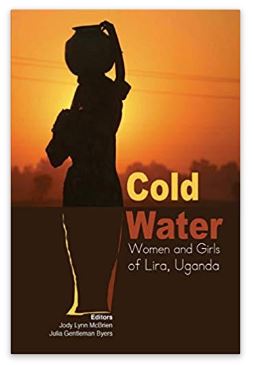

Note: This article draws heavily from the book Cold Water, Women and Girls of Lira, Uganda, edited in 2015 by Jody McBrien and Julia Byers and contributed to by Okite Emma, who assisted us in recruiting our first students (quotes reference page numbers from the book). It is named “Cold Water” to honor the women world-wide who spend hours each day collecting water for their families.

Note: This article draws heavily from the book Cold Water, Women and Girls of Lira, Uganda, edited in 2015 by Jody McBrien and Julia Byers and contributed to by Okite Emma, who assisted us in recruiting our first students (quotes reference page numbers from the book). It is named “Cold Water” to honor the women world-wide who spend hours each day collecting water for their families.

“Tribes delegate the job of gathering water for the community not to the wife, husband, or son, but to the girl child.” (p 129)

“Women are the bearers of life, not only through childbirth, but through their connection to water and carrying it long distances for cooking, bathing, and cleaning. When they unite, women can also be a formidable force for change.” (p xvi)